Improving the Efficiency of Biogas – Power from Poo Research in Nepal

February 26, 2019

As part of our efforts to support and encourage young Australians in study, careers and volunteering in international agricultural research, the Crawford Fund State Committees proudly support our International Agricultural Student Awards. The 2018 recipients of these Awards were announced in May, and we are enjoying the process of sharing the journey of these 22 dynamic Australian tertiary students as they gain international agricultural research experience and expertise.

Throughout 2018 and the early part of this year, the successful Award recipients will travel to their host countries to research and explore their chosen topic areas. You can follow their progress here on the Crawford Fund website and read more about their findings, learnings and any challenges they encounter.

To-date we have featured the experiences of University of Western Australia student, Christian Berger; Queensland University of Technology PhD candidate, Thomas Noble; University of Melbourne student, Kimberly Pellosis; Luisa Olmo from the University of Sydney; Rachael Wood from Charles Sturt University; University of Melbourne student Ziyang Loh; Lucinda Dunn from the University of Sydney; Jessica Fearnley from the University of New England; the Australian National University’s Jacinta Watkins, and most recently, University of Queensland Honours student, Tamaya Peressini.

Now, thanks to The Crawford Fund SA Committee, we present to you, University of Adelaide student Mathu Indren’s experience at a biogas plant in Nepal as part of his PhD research project.

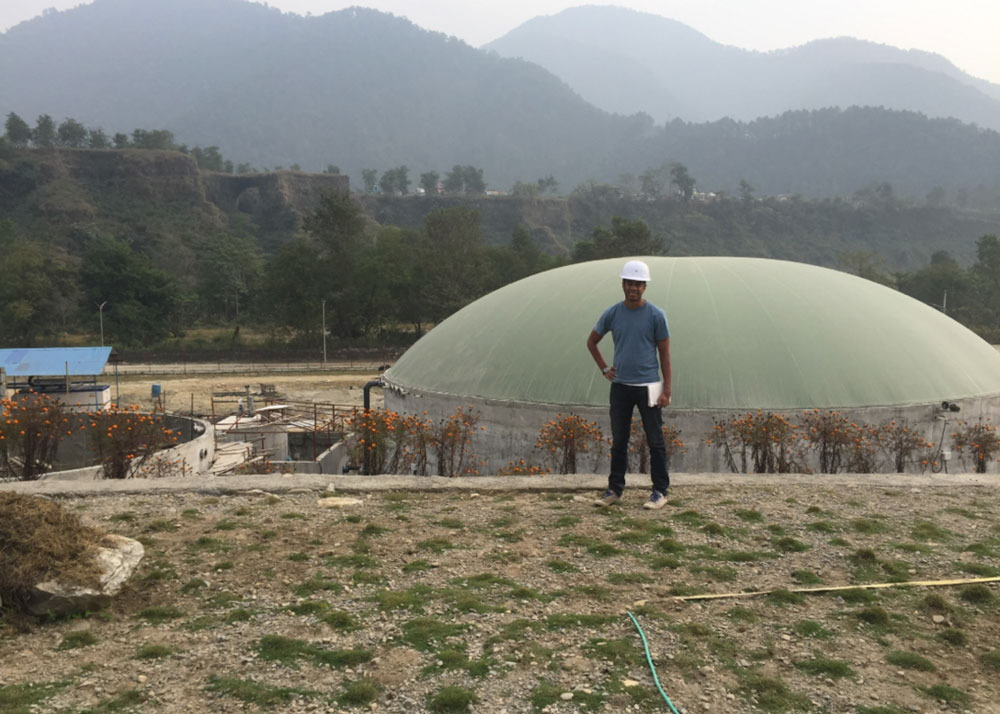

Mathu in front of the anaerobic digester 20km outside of Pokhara, Nepal. The biogas is contained within the green balloon before it is purified into biomethane.

In November 2018, The Crawford Fund facilitated Mathu Indren’s four-week research trip to Nepal, where he worked with two private companies, WindPower Nepal and Gandaki Urja at their joint venture biogas plant. The plant is located 20 kilometres from Pokhara in central Nepal, and processes 45 tonnes of cattle, swine and poultry manure a day.

Biogas is a form of renewable energy produced from the decomposition of organic material by microorganisms in an environment that is anaerobic (or without air). Engineered systems for biogas production are termed anaerobic digesters or bio-digesters.

“My PhD project is focussed on improving the efficiency of biogas production from manure by adding in biochar into the anaerobic digesters,” said Mathu.

“My goal for this research trip was to develop an understanding on the feasibility of using biochar in both domestic and large-scale digesters in Nepal and to understand the operational considerations involved in running a biogas plant.”

The use of manure for biogas production is not a new idea for Nepal as there are approximately 30,000 domestic scale digesters (2-8m3) in the country, however, the idea of a centralised, large-scale plant is a new idea for Nepal, with the first constructed in 2017. The plant in Pokhara is the country’s latest and the largest at 2700 m3.

At this scale, the purification of biogas, which contains methane and carbon dioxide into a gas that contains 97 per cent methane, termed ‘bio-methane’ becomes economically feasible in Nepal.

“Bio-methane production is gaining popularity in Europe and has been used in India. Despite Australia’s significant livestock population and several biogas plants we do not have a single bio-methane plant,” said Mathu.

“This research trip exposed me to some challenges and opportunities that I would not have been able to imagine. Within my first week in Nepal my colleagues and I travelled to various farms as they negotiated prices to purchase manure from their livestock.”

“Despite the manure being produced by their livestock being a real nuisance for farmers to manage, the farmers were never willing to give it away free.”

“In addition, many of these farms did not have easy access for trucks, making manure collection troublesome, and the cattle farms in the area were small and housed just 10-15 cows with the largest containing 200 cows, so a dedicated feedstock manager was needed to manage collection of manure from all of the farms to ensure a consistent supply,” said Mathu.

“I also developed an understanding of environmental benefits due to improved manure management that centralised anaerobic digesters can offer,” said Mathu.

Cows and a pile of manure ready to be collected and transported to the biogas plant

Centralised anaerobic digesters offer farmers another management option beyond selling it as a fertiliser and using it themselves.

Farmers are able to sell their livestock manure as a fertiliser for two-three months of the year. At other times, it is spread onto land or stockpiled. As the average land holding for farmers is small (around 0.7 hectares) there is limited space for manure to be applied. When manure is stockpiled, odour nuisance becomes an issue, with several farms forced to move due to odour complaints from neighbours.

“We also visited several farms which had domestic digesters installed. Many of these digesters were not being used and my colleagues stated how farmers did not always operate digesters in winter and some are eventually abandoned due to low gas yields. This highlighted the need for education and support that must be given to biogas plant users in order for them to have a consistent supply of biogas,” said Mathu.

“I was able to share my research findings on how biochar can be used to benefit anaerobic digesters, which was met with great enthusiasm. As a result, we were able to develop a research plan to test the increases in biogas yield when biochar created from an invasive species Eupatorium adenophorum sprengel (known in Nepal as “banmara”) is added into an anaerobic digester.”

“Overall, this experience was incredibly valuable and greatly broadened my research experience. The insights gained from this experience will help to design studies that are relevant to biogas producers both in developing countries and in Australia,” concluded Mathu.

0

0